Project Mālama Kaho’olawe

If you plan for a year, plant kalo

If you plan for ten years, plant koa

If you plan for one hundred years, teach the children

-Puanani Burgess

Produced by the Pacific American Foundation in partnership with:

Kaho’olawe Island Reserve Commission

Polynesian Voyaging Society

Protect Kaho’olawe Ohana

Curriculum was developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education S362A060059, although it does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. ©2008 – 2020 All Rights Reserved, The Pacific American Foundation. For Educational Use Only, under the limited circumstances of the Fair Use Doctrine.

As a Teacher, Parent or Student, you may print a copy of sections, within reason, of our educational materials for non-commercial use only. Materials may also be purchased, and donations are accepted by our nonprofit organization.

With our Malama Kaho’olawe curriculum we learn from Kaho’olawe and how to become involved in projects that ‘heal at home.’

The island of Kaho’olawe provides a unique opportunity to explore our connection to the ‘aina (land and sea). Without any of the trappings of modern civilization, the land reveals itself in a raw and beautiful way – the numerous rock remains of house sites, petrogyphs, and heiau (shrines) takes us back to a time when Hawai’ians lived harmoniously with the land and sea, growing ‘uala (sweet potato) in the uplands and harvesting fish from the island’s bountiful reefs.

The loss of topsoil and damage to the island’s cultural sites and native ecosystems have taught us much about the way that human activities impact the environment.

Since the return of the island to the State of Hawai’i, the healing and restoration have taken place provide an inspiration to all of us and awaken a spirit of aloha ‘aina that can guide us to care for our home island.

Since students may not actually visit Kahoʻolawe, our video series takes them along on a high school huakaʻi (field trip) to the the island where they explore significant island sites and learn from knowledgeable people along the way. It can be watched here online, or, viewed on TV by the whole family on ROKU TV on the Malama Channel.

Hawai’i Olelo WORD LIST, MAP and Reflection Questions here!

![]() The Hawai’ian band is a traditional representation of Hawaiian gods, na’aumakua (guardian ancestors) and all our kūpuna (elders) who came before us, the clouds, mountains, earth, and sea. Along the side are petroglyph figures representing some of the petroglyphs found on the island of Kaho’olawe.

The Hawai’ian band is a traditional representation of Hawaiian gods, na’aumakua (guardian ancestors) and all our kūpuna (elders) who came before us, the clouds, mountains, earth, and sea. Along the side are petroglyph figures representing some of the petroglyphs found on the island of Kaho’olawe.

The Ka Palupalu o Kanaloa (Kanaloa kahoolawensis), a critically endangered plant species, reminds us of the need to mālama Kaho’olawe. The only remaining plant in the wild clings to the cliffs of ‘Ale’ale–a seastack off the southern coast of Kaho’olawe.

The Ka Palupalu o Kanaloa (Kanaloa kahoolawensis), a critically endangered plant species, reminds us of the need to mālama Kaho’olawe. The only remaining plant in the wild clings to the cliffs of ‘Ale’ale–a seastack off the southern coast of Kaho’olawe.

The complete (all grades/topics) curriculum in pdf is a 150MB file of 512 pages.

The complete (all grades/topics) curriculum in pdf is a 150MB file of 512 pages.![]() View and Download the full PDF

View and Download the full PDF

For individual grades or topics, use the tabs at left.

<<<<<<<<<

Units include:

Unit Map – an overview for the teacher of focus questions, key concepts, and assessments for each lesson

Rubrics – unit summative assessments for students’ performance on culminating projects

Student Assessment Overview – an overview for students that provides expectations and a list of journal pages that they will complete as formative assessment.

Instructional Activities – Each unit includes four to five lessons that are designed to be taught sequentially, and include Nā Honua Mauli Ola (Hawaiian Guidelines for Learning),materials lists, and everything you will need to use our lessons or create your own with our materials.

Teaching suggestions included in each lesson and the estimated time for completing the lesson have been refined based on a field test that was conducted with teachers for most of the lessons during the course of the project. The teaching suggestions are designed to help students meet the standards, but they are, of course, only suggestions since there are many different and effective ways to approach the activities.

Grade 8

Grade 8

Ka Piko – Voyaging

Why was Kaho’olawe an important location for training navigators?

How do we carry on voyaging traditions today?

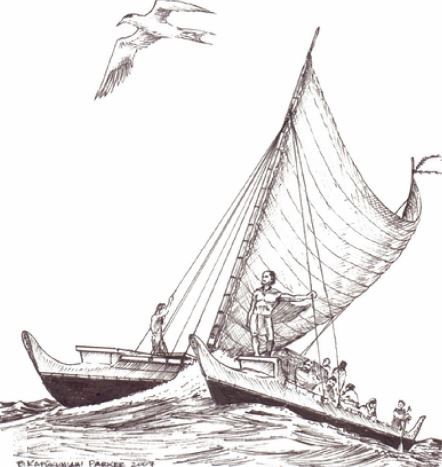

The island of Kaho’olawe served as a training site for ancient navigators. Historically, Kaho’olawe was the prime location for ocean voyaging and its position in the Hawai’ian archipelago allowed navigators to study the stars, sunrise and sunset, winds, and ocean currents.

The island is the piko (center) of the Hawaiian island chain and “the point of arrival and departure for canoes journeying to and from the southern islands” (Reeve, 1995).

Lesson 1: Ka Piko – Center of Voyaging

Lesson 1: Ka Piko – Center of Voyaging

Students discover the relationship of Kaho’olawe to early voyaging through oli (chant), mo’olelo (story), videos, and presentations. They identify key sites significant to the training of navigators on Kaho’olawe maps, and share what they learn through illustration and writing.

Lesson 2: Ulu ka La, ka Mahina – Sun and Moon

Students explore the many relationships of the sun, moon, and Earth and how they affect seasons, tides, or weather conditions. We’ll learn about how navigators forecast the weather.

Lesson 3: Makani and Kai Ko – Winds and Currents

Students conduct an experiment to find out how atmospheric and ocean convection currents are created. We’ll design and build model canoes and observe how the canoes move under simulated conditions.

Lesson 4: Ka Lani Pa’a – Celestial Navigation

Students explore how to use a star compass for celestial navigation, comparing forms of ancient and 1nodern-day instruments used in navigation. We’ll play a Ka Lani Pa’a game to reinforce how navigators use the star compass.

Lesson 5: Voyaging Traditions Ho’ike

Students work in teams to produce a five minute ‘newscast” about the significance of Kaho’olawe as a site for training navigators. Students apply their knowledge and creativity to write and illustrate a story for younger students. They help to carry on voyaging traditions by sharing their knowledge through a community ho’ike (exhibit). Classes are encouraged to visit sites (virtually) that are significant to voyaging on their island, and take part in community projects to build canoes and preserve navigational sites.

Social Studies – Grade 9-12

Hoʻi Ho: History & Civics

We begin with the history – the events that led up to the end of military use of Kahoʻolawe.

The story of the return of the island to the State of Hawaiʻi is a compelling one that allows students an opportunity to see a dynamic interplay of cultural / social, economic, and political forces. It is a time that gave birth to the Hawaiian Renaissance—a reawakening of Hawaiian cultural practices, site restoration, language immersion programs, voyaging, and music.

We then discuss the movement to stop the bombing of Kahoʻolawe, and how it lead to social, political, and economic changes in Hawaiʻi. We investigate what is being done to heal the island today?

Students explore this question through research, metaphors, fine arts, timelines, and interviewing community members. They summarize what they have learned in a final paper that answers the unit essential question. Students also work on culminating projects using art, music, or theatrical productions to depict social, political, or economic causes and effects of change that led to the healing of Kahoʻolawe.In the first lesson, Aloha ʻĀina, a DVD produced by the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) introduces students to Kahoʻolawe. We’ll read excerpts from George Helm’s journal and a letter from PKO to President Carter as an introduction to the movement to stop military use of the island. Students conduct research to identify causes and effects of significant changes that led up to the events described in the letter and journal.

In the second lesson, Different Perspectives, students use metaphors in the form of graphic symbols to reflect on and compare a Hawaiian perspective with the perspective of the U.S. military regarding use of Kahoʻolawe. Students work in groups to express these perspectives and compare and contrast them.

The third lesson, Hoʻi Hou – To Return, challenges students to create a large timeline with string and event cards in the classroom. The timeline dates from 1600 to 1994, when Kahoʻolawe was turned over to the State of Hawaiʻi. Students work individually to research significant events from the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 until the return of the island to the state in 1994. They interview adults and write journal reflections to describe how those events were significant in the Hawaiian Renaissance.

In the fourth lesson, Healing of Kanaloa, students play a game that focuses on the value of laulima (cooperation) and the interconnectedness of all of us with the ʻāina. They summarize and discuss what they read about the navy cleanup of Kahoʻolawe and the activities that are being conducted to heal the island and revitalize Hawaiian cultural and spiritual practices, such as the celebration of Makahiki to honor Lono, the Hawaiian god of agricultural fertility, medicine, and peace. Students work to complete culminating unit projects that they present to others in a hōʻike (exhibit) for the community.

| Values Emphasized: Aloha ʻĀina (Love of the Land and Sea) Hoʻokuleana (Taking Responsibility), and Mālama (Caring)

|

Biology

To Balance

What can we learn from Kahoʻolawe & modern science that would help us to reduce our school’s carbon footprint?

Lesson 1: Earth Energy Moʻolelo

Lesson 2: Carbon Cycles

Lesson 3: Carbon Budgets and Footprints

Lesson 4: Lessons from Kahoʻolawe

Lesson 5: Hoʻokaulike- To Balance

Earth Science

Lesson 1: Hiki Mai Ka Lā- Here Comes the Sun

Lesson 2: Makani and Kōī Au – Wind and Flowing Currents

Lesson 3: Calling Back the Clouds

Lesson 4: Red Clouds

Lesson 5: Mālama ʻĀina

Grade 7

Grade 7

Kei Kai – Marine Science

How can we malama (care for) our ocean environment and have enough fish for today and for future generations?

Students learn about the nearshore fisheries populations in Hawai’i. They compare traditional Hawai’ian fishing methods to modern methods and present their findings, explaining what we can learn from the Kaho’olawe marine reserve to malama (care for) fisheries today and in the future.

Lesson 1: Ke Kai Kapu- A Marine Sanctuary

Lesson 2: Fishing Around with Technology

Lesson 3: Taking a Watershed-Based Approach

Lesson 4: Investigating Marine Ecosystems

Lesson 5: Mālama i Ke Kai

Na Oli (Chants)

Ke Oli

Early Hawaiians recorded their literature in memory, not writing. They composed and maintained an extensive oral tradition, a body of literature covering every facet of Hawaiian life. Chants, called oli, recorded thousands of years of ancient Polynesian and Hawaiian history.

Oli also recorded the daily life of the Hawaiian people, their love of the land, humor, tragedy, and the heroic character of their leaders. Performing an oli, involved special talent and training.

Today, Hawaiian culture continues to thrive through oral traditions that are perpetuated through legends, hula, and oli. It is common for school and community groups to prepare and present oli for special occasions or events. This form of oli is called Hawaiian protocol or loina. Those who practice and present oli understand that it is conducted for a specific purpose and a specific audience.

The following passage describes loina and how it is used for specific situations.

What is loina (Hawaiian protocol)?

It is the right behavior conducted at the appropriate time by the proper people, presented to the correct recipients, toward a positive and significant end. Protocol almost always involves words, presented usually in the form of oli. Oli takes the power of words, themselves recognized as highly significant in Hawaiian and in many other cultures, and extends that power of words to a higher level that fulfills several functions:

- It focuses the attention of all participants to the task at hand.

- It evokes respect in the form of silence and attention on the part of the recipients.

- It prepares the participants to engage seriously in what will follow.

- It initiates a set of responses from those who know the protocol, and therefore sets into action a social process that unifies not only those who conduct the protocol but also all who are involved.

- It transforms the mood from the mundane and ordinary into something deeper and more important.

- It links all participants together and consolidates them into a unit.

- It links the participants to their surroundings via an enhanced sense of place.

- It expresses and confirms a living and vital Hawaiian culture, making each person a bit more appreciative of and more connected to these islands that we call home.

Protocol suggests that training and practice is involved, and indeed this is so. The practice is a traditional and oral one, with teachers passing the proper and expected behaviors to their students. Students and teachers in turn practice protocol with each other and develop comfort at conducting themselves in very specific ways that often demand exactly the right words and actions in a prescribed sequence.

Proper behavior and words are highly dependent on the situation. For example, the protocol for greeting a person of significance is different from the protocol of entry to a significant site and different from the protocol for presentation of an offering or gift. Whatever the situation, protocol is based on a foundation of values that are important to everyone, regardless of their ancestry and upbringing. These are fundamentals such as respect for others and for the land, an attitude of sharing and responsibility for maintaining a balance between self and society and between human beings and the rest of the universe.

Written by: Sam Gon III, Ph.D., Director of Science at the Nature Conservancy of Hawaiʻi and Chanter with the late Kumu John Keolamakaʻāinanana Lake

The Pacific American Foundation provides these oli that are noa (free-without restrictions) and kumu are encouraged to share these oli with their haumāna (students). The oli should be presented for a specific situation as described. A different set of oli will be taught to those who have a scheduled huakaʻi (access) to Kahoʻolawe. These oli are reserved for those who will access the island and are not intended for use anywhere else. As a result, the oli are not included in the curriculum but would be only taught during on -site orientation.

E Hō Mai

Composed by: Edith Kekuhikuhipu’uoneo’naali’iokohal

E hō mai ka ‘ike mai luna mai e

O nā mea huna no`eau no nā mele e

E hō mai

E hō mai

E hō mai

Grant us the knowledge from above

Concerning the hidden wisdom of songs,

Grant,

Grant,

Grant us these things

Kumu hula master and Hawaiian cultural and language expert, Edith K. Kanāka`ole (affectionately known as Aunty Edith), composed this oli (chant) for her hula troupe, Hālau O Kekuhi. The chant was originally performed by students at the beginning of class to request knowledge and wisdom from the ancestral deities to accomplish the task at hand.

Today, this oli is commonly used at the start of an event or small gathering to focus a group’s energies and ultimately carry out the kuleana (responsibility) they have undertaken. It is recommended that haumāna (students) use this chant to help them seek knowledge and clear their minds of any negativity.

E Ala E

Composed by: The Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation for the August 1992 healing ceremony on Kahoʻolawe

| E ala ē

ka lā i ka hikina I ka moana, ka moana hōhonu, Piʻi i ka lewa, ka lewa nuʻu I ka hikina, aia ka lā. E ala ē! |

Arise

the sun in the east On the ocean, the deep/dark ocean Climbing into the heavens the lofty heavens In the east, there is the sun Arise! |

Notes:

This chant begins a short time before the sun rises in the morning and must be continued until the sunʻs disc is fully above the horizon.

On Kahoʻolawe, the group forms a half circle and faces the sun as it slowly rises over the peak of Haleakalā on Maui. The other half of the circle represents all those kūpuna (ancestors) who have passed on and ʻaumākua (ancestral deities) that complete the circle. In essence, they are there to protect and guide the group as they begin a new day.

This oli is chanted early in the morning to aid the sun to rise. To chant, form a half circle facing the direction of the sunrise. The reason for the half circle is that in the other half of the circle stands all of the kūpuna (ancestors) who have passed on. The oli welcomes the new day and honors those who have come before us.

Note: Visitors to Kahoʻolawe greet each sunrise with this chant.

(Hand motions: Students cup hands and clap twice. On the third clap, they should open the palms of their hands. Repeat hand motions until oli is completed.)

Hiki mai ka Lā

From Pele and Hiʻiaka – A Myth from Hawaiʻi by Nathaniel B. Emerson (1915)

Hiki mai, hiki mai ka lā

Aloha wale, ka lā e kau nei

Aia malalo o Kawaihoa

A ka lalo o Kauaʻi

O Lehua

Here it comes, here comes the Sun

How I love the Sun in the sky

There below is Kawaihoa

On the incline of Kauaʻi

Is Lehua

BACKGROUND

Peleʻs sister Kapoulakinau danced this hula on the island of Niʻihau. It is considered one of the earliest of hula, a hula kiʻi.

This oli was shared with the Windward Ahupuaʻa Kūpuna by Anakala Kimo Awai of Hilo along with the Hilo districtʻs kūpuna. He also taught its motions. It is both a chant of welcome to the morning Sun in the sky as well as a request for inspiration from Ke Akua, the creation, or our ancestors.

Kunihi Ka Mauna

Traditional

| Kunihi ka mauna i ka laʻi e

ʻO Waiʻaleʻale la i Wailua Huki aʻela i ka lani Ka papa auwai o Kawaikini ʻAlai ʻia aʻela e Nounou Nalo ka Ipuhaʻa Ka laula ma uka o Kapaʻa ē Mai paʻa i ka leo He ʻole kāhea mai e. |

Tall stand the mountain in the calm

Waiʻaleʻale (as seen) from Wailua Pulled up to the heavens The water – channeled plateau of Kawaikini Obstructed by Nounou Concealed is Ipuhaʻa (hill) The uplands of Kapaʻa Hold not your reply No answering call comes back. |

Notes:

According to legend, when Hiʻiaka was on her way to fetch Lohiʻau on Kauaʻi, she encountered a sullen and inhospitable old woman who prevented her from crossing the Wailua River. In subtle language, Hiʻiaka uses this chant to show how she disapproves of the haughty conduct.

This oli serves today as an entrance chant, requesting permission to enter the hālau or place of learning. It also asserts that haumāna (students) are focused and prepared to learn. They leave all negativity at the door before entering.

Oli Ia Laka

Noho ana ke akua

i ka nāhelehele

i ʻalai ʻia e ke kīʻohuʻohu

e ka ua koko

E nā kino malu i ka lani

malu e hoe

E hoʻoulu mai ana ʻo Laka

i kona mau kahu

ʻO wau [mākou,

ʻo wau [mākou] nō, a!

The god resides

in the thick forest

that was hidden by the clinging mist

by the low-lying rainbow

O beings sheltered in the heavens

sheltered continually

Laka will confer growth on

her caretakers

Tis I [we] ’tis I [we] indeed, ah!

Oli Iā Laka

Traditional

| Noho ana ke akua i ka nāhelehele

I ālai ʻia e ke kīʻohuʻohu e ka ua koko E nā kino malu i ka lani Malu e hō ē E hoʻoulu mai ana ʻo Laka i kona man kahu ʻO mākou, ʻo mākou, ʻo mākou nō ē Aloha ē |

The god resides in the thick forest

That was hidden by the clinging mist by O beings sheltered in the heavens Laka will confer growth on her caretakers It is only us (who are humbly asking Aloha ē |

Notes:

This oli is often chanted before entering the forest. It requests permission to enter the forest and to guard the group after entering. Groups will use this chant just before a hike or if they are gathering plant material for their hula adornments.

Na ʻAumākua

Traditional (first part)

Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation (second part)

| Nā ʻaumūkua mai ka lā hiki a ka lā kau Mai ka hoʻokuʻi a ka hālāwai Nā ʻaumākua iā ka hina kua iā ka hina alo Iā ka ʻākau i ka laniʻO kihā i ka lani ʻOwē i ka lani Nūnulu i ka lani Kāholo i ka lani.Eia nā pulapula a ʻoukou ʻO [name of person or group] E mālama ʻoukou iā mākouE ulu i ka lani E ulu i ka hōnua E ulu i ka pae ʻāina o Hawaiʻi neiE hōmai i ka ʻike E hōmai i ka ikaika E hōmai i ka akamai E hōmai i ka maopopo pono E hōmai i ka ʻike pāpālua E hōmai i ka manaʻĀmama, ua noa. |

The ancestors from sun rise to setting From zenith to horizon The ancestors at our backs and fronts At the right hand of chiefsBreath in the heavens Utterance in the heavens Clear voice in the heavens Reverberating in the heavensHere are your children[Name(s) of person(s) or group] Watch over usIncrease in the heavens Increase in the earth Increase in the Hawaiian archipelagoGrant knowledge Grant strength Grant intelligence Grant understanding Grant foresight Grant powerCompleted, it has been set free. |

Notes:

This is a traditional chant calling to the ancestral deities to provide protection and guidance to a descendant or group of descendants. The first section of the chant is traditional. A premier Hawaiian cultural group – the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation – added the second half more recently. This oli recognizes the mana (power) of the words and the kuleana (responsibility) that is assumed when performing this chant.

Oli Mahalo

Composed by: Kehau Camara—

`U hola `ia ka maka loa la

Pü`ai ke aloha la

Küka`i`ia ka Hāloa la

Pā wehi mai nā lehua

Mai ka ho`oku`i a ka hālāwai la

Mahalo, e nā akua

Mahalo, e nā küpuna la ea

Mahalo, me ke aloha la

Mahalo, me ke aloha la

To spread forth, open up the most fine quality mat

Exchange/share as potluck or aloha

Exchange as greetings (between man and wife and

descendants)

To adorn with the lehua flower

From East to West; sunrise to sunset, we are

discoverers, navigators, take care of our ʻāina

We thank our creators

We thank our ancestors

We thank you with love

We thank you with love

This oli was composed as a greeting of thanks for hospitality, love, generosity and knowledge that is given to us. It also gives thanks to the beauty of the islands and our people. Hāloa is ever-lasting breath. The kalo plant is considered our ancestor that is cherished and preserved. Makaloa is the finest mat woven. It is considered higher quality than lau hala. The message is that it’s important for us to practice being “thankful” every day